Item

Gus Raymond Oral History, 2022/07/29

Title (Dublin Core)

Gus Raymond Oral History, 2022/07/29

Description (Dublin Core)

Self Description: "Oh, gosh, it's a long list as far as titles go. I am currently at the very end of my master's program for clinical mental health. So I'm a mental health intern. I also work full time in the school district, the local school district, as the director of prevention and intervention. I am a certified CADC for the state of Iowa, which means I'm, I'm a substance abuse counselor, and I have been for close to five years now. Gosh, I'm a trans man, I'm a husband, I'm a dad. I'm a dog dad. I used to be a chef, and now I just wear about 15 different hats and and try to do all the things that feel right to me to make the world better."

Some of the things we discussed include:

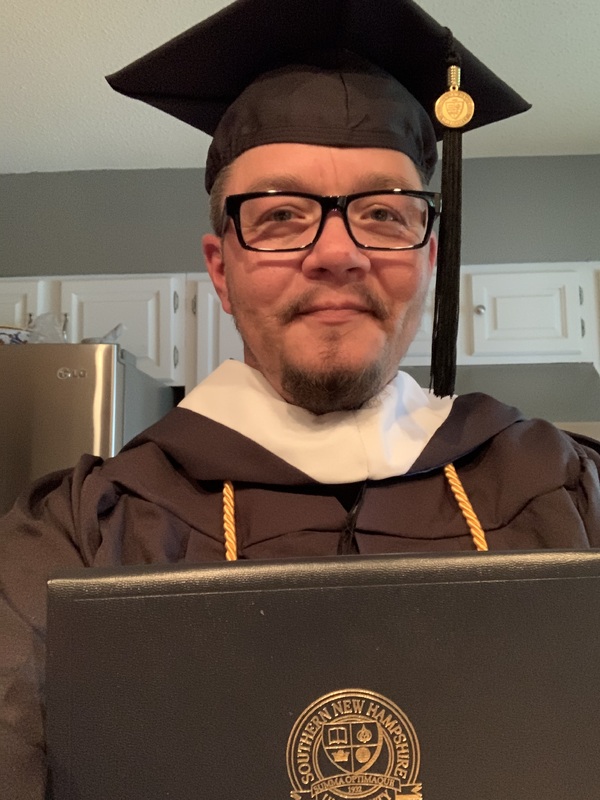

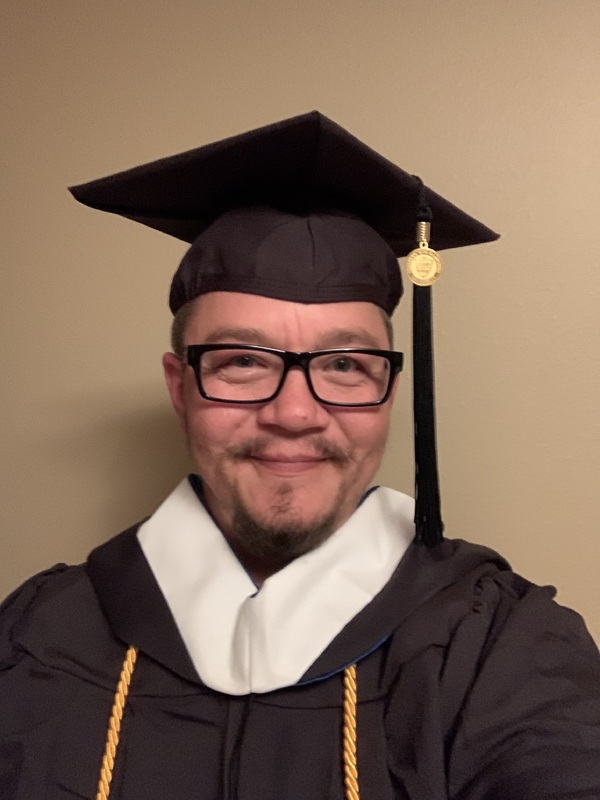

Finishing a BA during the pandemic, lost graduation.

Nearing the completion of an MA.

Working as an addictions specialist in community mental health.

Moving from long commutes to have face-to-face interactions with substance abuse clients to teleworking.

Working with rural clients who don’t have teleworking tools, like laptops or broadband; limited access to treatment and psychiatric institutions.

Client neediness and slippery boundaries.

Legal differences between clients who are suicidal and those who are parasuicidal (eg, comfortable with drinking themselves to death).

Feelings of helplessness as a clinician.

Forprofit healthcare systems that leave people feeling like no one cares if they live or die.

Medicalization and gatekeeping that comes with gender-transitioning; worse in rural USA.

Governor of Iowa, Kim Reynolds, returning COVID relief money to the federal government.

Moving from Community Mental Health to working for the school district.

The diversity in rural Iowa, 30+ languages spoken in a school system of a few thousand students; refugees and other trauma survivors ending up in the meatpacking industry.

Personal experiences of addiction and sobriety.

Coming from a military family with post Vietnam PTSD.

Hypervigilance as a maladaptive coping mechanism; hypervigilance as a superpower in the right context.

Father having had a heart attack in 2019 and the stressors of distance and the risks associated with visitation.

Difficulties visiting with stepchildren during the pandemic.

Small and occasional celebrations outside the home: celebrating Christmas in 2020; going out for wife’s birthday in 2022.

The loneliness of isolation.

Political rhetoric about masking as a freedom issue.

Feeling a need for advocacy even in the face of futility.

Anti-LGBTQ legislation.

Current framing of Monkeypox as a gay man’s disease.

The relationship between health and wellness; health as a human right.

Safety in passing as a cis man, and a loss of recognition.

Getting a needy rescue dog during 2022.

Other cultural references: Fauci, Twitter, Politician Steven Arnold King, Uvalde school shooting (24 May 2022), active shooter training in schools, SnapChat, Vietnam, novelist Stephen King

Finishing a BA during the pandemic, lost graduation.

Nearing the completion of an MA.

Working as an addictions specialist in community mental health.

Moving from long commutes to have face-to-face interactions with substance abuse clients to teleworking.

Working with rural clients who don’t have teleworking tools, like laptops or broadband; limited access to treatment and psychiatric institutions.

Client neediness and slippery boundaries.

Legal differences between clients who are suicidal and those who are parasuicidal (eg, comfortable with drinking themselves to death).

Feelings of helplessness as a clinician.

Forprofit healthcare systems that leave people feeling like no one cares if they live or die.

Medicalization and gatekeeping that comes with gender-transitioning; worse in rural USA.

Governor of Iowa, Kim Reynolds, returning COVID relief money to the federal government.

Moving from Community Mental Health to working for the school district.

The diversity in rural Iowa, 30+ languages spoken in a school system of a few thousand students; refugees and other trauma survivors ending up in the meatpacking industry.

Personal experiences of addiction and sobriety.

Coming from a military family with post Vietnam PTSD.

Hypervigilance as a maladaptive coping mechanism; hypervigilance as a superpower in the right context.

Father having had a heart attack in 2019 and the stressors of distance and the risks associated with visitation.

Difficulties visiting with stepchildren during the pandemic.

Small and occasional celebrations outside the home: celebrating Christmas in 2020; going out for wife’s birthday in 2022.

The loneliness of isolation.

Political rhetoric about masking as a freedom issue.

Feeling a need for advocacy even in the face of futility.

Anti-LGBTQ legislation.

Current framing of Monkeypox as a gay man’s disease.

The relationship between health and wellness; health as a human right.

Safety in passing as a cis man, and a loss of recognition.

Getting a needy rescue dog during 2022.

Other cultural references: Fauci, Twitter, Politician Steven Arnold King, Uvalde school shooting (24 May 2022), active shooter training in schools, SnapChat, Vietnam, novelist Stephen King

Recording Date (Dublin Core)

July 29, 2022

Creator (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Gus Raymond

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Link (Bibliographic Ontology)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

English

Education--Universities

English

Health & Wellness

English

Home & Family Life

English

Online Learning

English

Gender & Sexuality

English

Social Issues

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

father

mask

trans

bachelors

university

Contributor's Tags (a true folksonomy) (Friend of a Friend)

activist

addiction

Christmas

counselor

fatherhood

introvert

Iowa

loneliness

marriage

masking

mental health

queer

rural

school

student

therapist

trans*

transphobia

trauma

Collection (Dublin Core)

LGBTQ+

Lost Graduations

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

08/16/2022

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

03/08/2023

03/30/2023

05/04/2023

Date Created (Dublin Core)

07/29/2022

Interviewer (Bibliographic Ontology)

Kit Heintzman

Interviewee (Bibliographic Ontology)

Gus Raymond

Location (Omeka Classic)

Stormlake

Iowa

United States of America

Format (Dublin Core)

Video

Language (Dublin Core)

English

Duration (Omeka Classic)

01:41:05

abstract (Bibliographic Ontology)

Finishing a BA during the pandemic, lost graduation. Nearing the completion of an MA. Working as an addictions specialist in community mental health. Moving from long commutes to have face-to-face interactions with substance abuse clients to teleworking. Working with rural clients who don’t have teleworking tools, like laptops or broadband; limited access to treatment and psychiatric institutions. Client neediness and slippery boundaries. Legal differences between clients who are suicidal and those who are parasuicidal (eg, comfortable with drinking themselves to death). Feelings of helplessness as a clinician. For profit healthcare systems that leave people feeling like no one cares if they live or die. Medicalization and gatekeeping that comes with gender-transitioning; worse in rural USA. Governor of Iowa, Kim Reynolds, returning COVID relief money to the federal government. Moving from Community Mental Health to working for the school district. The diversity in rural Iowa, 30+ languages spoken in a school system of a few thousand students; refugees and other trauma survivors ending up in the meatpacking industry. Personal experiences of addiction and sobriety. Coming from a military family with post Vietnam PTSD. Hypervigilance as a maladaptive coping mechanism; hypervigilance as a superpower in the right context. Father having had a heart attack in 2019 and the stressors of distance and the risks associated with visitation. Difficulties visiting with stepchildren during the pandemic. Small and occasional celebrations outside the home: celebrating Christmas in 2020; going out for wife’s birthday in 2022. The loneliness of isolation. Political rhetoric about masking as a freedom issue. Feeling a need for advocacy even in the face of futility. Anti-LGBTQ legislation. Current framing of Monkeypox as a gay man’s disease. The relationship between health and wellness; health as a human right. Safety in passing as a cis man, and a loss of recognition. Getting a needy rescue dog during 2022.

Transcription (Omeka Classic)

Kit Heintzman 00:00

Would you please state your name, the date, the time, and your location?

Gus Raymond 00:04

Yes, I am Gus Raymond. It is July 29th 2022. In my time zone, it's 8:38am, and I am in Storm Lake, Iowa.

Kit Heintzman 00:15

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded and publicly released under a Creative Commons license attribution noncommercial sharealike?

Gus Raymond 00:25

Yes.

Kit Heintzman 00:27

Thank you so much. Would you please start by introducing yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening? What would you want them to know about you?

Gus Raymond 00:33

Oh, gosh, it's a long list as far as titles go. I am currently at the very end of my master's program for clinical mental health. So I'm a mental health intern. I also work full time in the school district, the local school district, as the director of prevention and intervention. I am a certified CADC for the state of Iowa, which means I'm, I'm a substance abuse counselor, and I have been for close to five years now. Gosh, I'm a trans man, I'm a husband, I'm a dad. I'm a dog dad. I used to be a chef, and now I just wear about 15 different hats and and try to do all the things that feel right to me to make the world better.

Kit Heintzman 01:27

Would you tell me a story about your life during the pandemic?

Gus Raymond 01:31

Oh, my gosh, what an episode this has been. And, and I say that currently, because it still feels very much like it's currently ongoing. I have some extended family members that are dealing with yet another round of COVID as we speak. As a matter of fact, we don't have our, my stepdaughter this week because she and her siblings and aunt all contracted COVID again. You know, I think the hardest part, because I was so used to counseling in a face to face environment. You know, I had a 45 minute drive to my office every day, normally, and I would see clients back to back to back all day long every day. And then all of a sudden, everything stopped. And kind of on a dime, we had to figure out how to put ourselves together at home, break down all these rules about all the new telehealth stuff because it's not something you typically do with substance abuse counseling. While I'm in the middle of the master's program, like the first chunk of it, and it was just mind blowing, I must have worked in four different rooms in my house before I finally found the right setup that had like enough Wi Fi, also enough privacy from the rest of my family because we're all stuck here. And then really, really getting frustrated because my my clients you know, this is storm like Iowa, we are kind of in the middle of nowhere. And my my clients are rural folks for the most part, and they don't all have broadband and laptops and smartphones and you know iPads, and and so it was a serious struggle to try and figure out how to get them in the right place in the right kind of accepted modality of communication while also watching them suffer, you know, and try really hard not to relapse in many cases and just throw in the towel in other cases and be totally helpless to help them. And I and I think that first probably three months or so of that solid telehealth stuff was just... it's hard to even remember it. It was it was mind boggling. I lost a couple of clients you know all while juggling your own stuff, trying to figure out your own thing. Trying to acclimate to this new scary world and and just sort of being like, surrounded by doom scroll all day every day, so that's my prominent memory from the early part.

Kit Heintzman 04:37

Do you remember when you first heard about COVID-19?

Gus Raymond 04:43

I do actually my wife and I were just chatting about that yesterday because monkeypox. I can't tell you precisely where I was, but I do remember feeling like reading some news articles and going hmm what is this weird disease that's going around, like what is happening, there's a virus, it's kind of off in the corners. Everybody's acting all nonchalant. And I remember telling her, I don't know, this doesn't feel good. I think this is gonna get out of control really fast. You know, and she's the eternal optimist and was like, Oh, it'll be fine. Everything's fine; it's way over there. Two seconds later, it's somewhere else; two seconds later, it's even closer, is what it feels like, and then just boom, you know, explosion, I think we were talking about it in like, December, January, and then all of a sudden, you know, it was March and everything shut down. And I think what I remember the most about that is how, how sad she got for a little while. You know, and you tried to cover it with this, like, ooh, we're stuck at home together, like, yay, we get to work from home and do all our things. You know, but after about three days, you're like, Okay, this is weird; this doesn't feel good. And, and as I said, because we were listening to some radio stations on the way to our event yesterday. You know, here's all this talk about monkeypox, and everybody's trying to put it in this gay men category, which feels grossly familiar, as a tactic for making people not worry. And, and I keep having that same feeling like, I don't know, I don't know if this is COVID fatigue, or just some sort of weird, I'm alert to viruses at this point, kind of sixth sense, or what, but I don't feel terribly confident about our ability to handle this one, either at this point.

Kit Heintzman 06:56

You'd mentioned noticing your wife sadness in the beginning, can you tell me about some of the ways that one comes to notice that. What changed that, provoke the like, oh, there's sadness here?

Gus Raymond 07:09

You know, I think it's just because she's generally such a positive hopeful person without being Pollyanna-ish. You know, I mean, she's just this really light, not grotesquely happy, but just just so pleasant to be around, and so comforting to be around. And I always feel so much joy when we're together, even when we're not really doing much of anything, but sitting on opposite ends of the couch doing our stuff. And there was a heaviness to just about everything. And I think that was just sort of true, in general, especially in the early to mid part of 2020. Is it just, it just never seemed like it was ending, it just kept getting worse. And like, you'd start to go like, Okay, if things are getting better, no, just kidding. Here's another round of numbers. And I just remember seeing her just sort of lose that light and lose that energy and start to get really tired. And it just made me feel so sad, because she's always so hopeful. And there wasn't anything I could do. I couldn't, I couldn't really help her. You know, there are only so many books and so many things you can go do and so many things I can bring to her. She's struggling to teach, and I'm struggling to do my job, and it just got very heavy and very tiring.

Kit Heintzman 08:38

To the extent that you're comfortable sharing, would you say something about your experiences of health and healthcare infrastructure prior to the pandemic?

Gus Raymond 08:46

Well, as a trans man, that's a loaded question, isn't it? You know, from from my own identity hat, I get really disappointed in our health system because my earlier transition, like the first couple of years, were extremely difficult. There's an immense amount of gatekeeping. I'm really lucky that that I started transition several years before the pandemic, because I think that would have been just a nightmare. Because it was hard enough as it was, you know, you have to run all over the place and get everybody's permission and justify your existence to this psychologist and that counselor and this doctor and that doctor and and locally, no doctor would see me. We certainly didn't have any LGBTQ specialists, let alone anyone that specialized in hormone replacement therapy or or any other trans related medical care. Heck, they wouldn't even see me for not directly trans related things. So I had to drive close to three hours to get any kind of care at all, and so with all that gatekeeping, it was really, really burdensome and lonely. And then from the professional hat, you know, as someone who works in the mental health industry, alongside medical folks, you know, trying to help clients who happen to be gender expansive or, or transgender, and help them go through this process and be really frustrated as a trans person having to follow things like W path that are inherently, I would say detrimental, for a big chunk of it to the very people that theoretically is helping, I get real frustrated and real fed up with the system. And then you throw in pandemic life, and it's just like I don't even know what to call it. I don't know what to call it, it was just incredibly frustrating and incredibly burdensome. And I'm lucky now, I have a great deal of privilege at this point, because we do have a doctor now that specializes in LGBTQ and trans individuals and is willing to do you know, the monitoring of my hormone replacement therapy, but you know, I don't have to drive three hours anymore unless I need something else, something specific, you know, a surgery or things like that. But it is an incredibly cumbersome, slow moving, dysfunctional system.

Kit Heintzman 11:54

Pre-pandemic, what was your day to day looking like?

Gus Raymond 12:00

Immensely busy. I worked, I think, gosh, it's hard to remember almost, it's like a whole different world. I was working two days a week in our local office and three days a week in our head office, which is, like I said, about 45 to an hour away. And so several days a week, I was on the road very early driving to Spencer, which is where our head office was working for community mental health agency. Trying to, let's see, I was finishing my bachelor's at that point as a 40 something year old person. You know, juggling a lot of things. And, and yet, I remember at least maybe tainted from all this pandemic stuff it felt later and more hopeful, and, you know, stupid, busy, but like I was getting somewhere. And I could be a little rose colored glasses, I'm not sure. That's my perception at this point. And it just felt good. You know, I was doing the things I wanted to do. I was trying out the people I wanted to try and help for now. And, and my wife and I and my family had created this pretty good system of balance. And and then I was just about to finish my bachelor's degree in late April, early May of 2020. And of course, everything had crashed by then. You know, it sort of feels like the health version of the Wall Street crash or something like, you know, going through a health Great Depression.

Kit Heintzman 13:55

How did how did some of that change once the pandemic hit?

Gus Raymond 13:59

Everything changed, everything changed. You know, you're suddenly restricted to where you can and can't go. Everybody is in this, you know, varying levels of either being absolutely defiant in the face of a global pandemic and acting as if not one thing is wrong, and everybody else is nuts. Or, you know, two, all the way to the other end of the spectrum where people are in an absolute panic and terrified to leave their homes. On a humorous note, I will say the sort of new perks you get, trying to do daily things like shopping really convenient to just pull up curbside and have somebody load stuff in your car and take off pandemic or not, that's a perk. If I'm going to try and be generous, I think the level of innovation that happened for things like that, I mean, I was being flippant, but, you know, trying to find ways to help people acclimate and, and stay safe and deal with it. I mean, that part was pretty amazing. I think what's the most disappointing is how fast we want to try and go back to normal when I'm not real sure, normal was working in the first place, and never really felt normal to me. I got wandered off on a sidetrack there, but...

Kit Heintzman 15:43

Fun facts about oral histories, there are no sidetracks like, everywhere you go is perfect. You really can't do anything wrong.

Gus Raymond 15:51

The, that'll make the squirrels in my head, I'm pretty happy. Nver have to concentrate and just go somewhere.

Kit Heintzman 15:59

What happened with your degree?

Gus Raymond 16:02

So, you know, I keep wanting to brush that off. Like, it's not a big deal. And to a point, it's not a big deal. You know, in the greater scheme of life, it's not that big of a deal, but I was finishing my bachelor's degree as I said, as a 40-something, I can't do the math anymore, but I had gone back to school after a very long, very detoured trip towards my bachelor's degree. And I started school. I think at the end of 2016, no, at the end of 2015, I went back to college and then had some fits and starts due to divorce and some readjustments and transition, you know, I apparently can't just do one or two things at a time, I've got to do like 15. And I had been at the local college, in person, normal student, you know, working around my class schedules and such, and then divorced bombed. And then, you know, had to figure out, I did attempt to go back to that school, but my ex wife worked at the school, and it was just complicated. So not a fun place to be. I took a little break, I searched around, finally found an online university that I felt wasn't a complete crock and dragged myself through that process, which was weird for a semi old fart, who had not really done a whole lot of online schooling in his life. And who had just been used to being in person face to face doing pretty traditional college level stuff. And at the very end of that ridiculous journey that I had worked really hard for and was feeling really proud about, the world stopped. And instead of all the grand plans I had of going to New Hampshire to attend my ceremony, we didn't even have a virtual one because everything was in such chaos. I mean, we were three or four months into the early part of the pandemic, and the school couldn't even like, they were like, You know what, we'll figure it out next year. Like, this is just too much for everybody. And at the time, I remember thinking of course... um I think on one hand, it was perfectly understandable that everything got, you know, just sort of frozen in time there a little bit, but at the same time, as someone who spent a really long period of my life taking a very winding way to that moment, it was incredibly sad. You know, I finally achieved my bachelor's degree, which I suppose to some people doesn't sound like a big deal, but to me, it was a pretty darn big deal because younger me never thought I could do something like that. Both ability and opportunity wise. And I finished with a 3.76 GPA, and then a completely foreign experience and then didn't even get to graduate. I mean, obviously, I graduated, but you know what I mean. So I felt like a little kid; I waited till my wife was at home. At some point, I don't know when it even was, it was much later in 2020, I think the world was trying to go back to normal already. And my regalia had shown up, you know, because of course, I ordered it anyway, because by golly, I was going to have that hat. Even though everybody looks like a dork in that hat, I really wanted it. Matter of fact, no, no, I finally put it away. It was sitting next to my desk for a really long time. So I'm, you know, dressed myself up, like a little kid, took a bunch of graduation photos of myself. I had honor cords, and you know, like, that was a big deal. And when they did finally get around to like, oh, last year's folks, we're going to do a virtual graduation for you, and, you know, by that point, I was like, forget it. I've already started my master's program, I'm doing 15 other things, you know, they threw us back into the office in August of 2020. Like, you know, Iowa did not, in my so humble opinion, manage the pandemic terribly well. They were dead set on just making it a blip. And then, you know, gotta get back to normal, got to earn our money, got to do our stuff. Forget all the rest of you. And so I was just up to my eyes at that point, I was like, I can't go to New Hampshire in the middle of all of this. Plus, I'm not going all the way to New Hampshire in the middle of all this. The rest of you are trying to go back to normal, and I'm like I don't think so. I'm not particularly immunocompromised or anything, but it just, I don't know, I'm even a bit more of a, and I totally flippantly use the term germaphobe. Not technically speaking, but, you know, one of those folks, it's like a little bit moved out by germs and stuff. And so, you know, the thought of getting in a plane that I don't like anyway, surrounded by people and the same air... nah. I'm good; I'll just take selfies, look like a goofball in my regalia. And so let me tell you how, absolutely, like squinty eyed I am at the end of my master's program at this point, because COVID is such a resurgence for the 9,000,000th time. And, and my university I attend Adler University in Chicago, obviously, mostly virtually. And they're kind of going back to like, well, I think we should have masks in the building. And they've they've handled this really well, if anything, we got irritated because they were a little too conscious in our opinion. At one point, we were like, really, can we have our residency program. Like I went to Chicago anyway and rented an Airbnb with three other students in my cohort because we had a residence week, one darn way or another. And it was a blast, and Chicago is home to me. So I was like, I'm not missing this trip. I don't care what you do. But now at this point, I feel like deja vu, right, like, I feel like I'm approaching this graduation again, with like, numbers going up and monkey pox happening and, and in particular, Chicago is struggling with monkey pox. And I'm just like, really, really... I'm 48 years old. I am this close to achieving my master's degree in October. My classes are done in four weeks. All I have left is the rest of my internship, and I'm done. Well, and some pretty hefty exams, talk about those. And I feel like it's coming again. I feel like they're gonna say, for the safety of all, we're gonna move this virtual. And I cannot tell you how badly I want to walk physically across that stage. It has taken so much for me to do this program. I work a full time job, basically a full time internship and school. And, you know, of course, probably half responsible for the amount of work I do at once. But, you know, not just limping along at one class a semester or anything. I'm in a hurry, darn it, so I have several classes. And it just feels like don't do this to me, universe. Pretty please, I thought we are on the other side of this equation for me, like the majority of my life, the first half of my life, probably even two thirds, stunk. And I'm lucky to be alive. And I'm in this period now, in the last five years or so that have just felt like a whole new life, a whole different life. Between transition and being remarried and actually being someone who like achieves things and succeeds, which is a completely foreign concept for me. And to have that, like, feel like it's this close to being loosied right out from underneath you as you kick the football. It's just like come on, and I'll manage it, whatever, I'll handle it, I always handle it. That's how I got here. But it just feels like I just I want that piece. Even if it's ridiculous, even if I'm the oldest person on the stage, probably I don't care. I want that. I want my honor cords. I'm still at a 3.7 something. Like, in the middle of all this in the middle of a pandemic, you know, full time jobs, left community mental health because it was eating me alive. You know, now work for the school district, which will probably eat me alive, but right now still feels pretty good. You know, all this stuff, I'm this close. Don't do that. Please don't do that. I'll handle it. But I'm not feeling as hopeful as I used to. I guess. Then yet my ever optimist wife is like it'll be okay. She's so cute. She's the sweetest thing.

Kit Heintzman 26:27

What brought you to do work in community mental health and addictions?

Gus Raymond 26:34

Well, that aforementioned previous life, for sure had a lot to do with that. Sort of unbeknownst to me, though, because I did not intend to be a therapist. As a matter of fact, I think one of the lessons I've learned over the last several years is to stop saying, "I'm never going to do such and such." Because here I am doing such and such, inevitably. And if I could turn that into, I'm not gonna win the lotto and then win the lotto, I totally would, but apparently, it doesn't work that way. I, I spent the majority of my previous life, which doesn't even refer to pre-transition, it's just that like screwball version of existence I had in food service, high end catering. Honestly, just about everything I get my hands on, but the majority of it was in the food service world. I mean, I even worked for, I shouldn't say the name of the company, a really high end, prominent, well known catering company that does Hollywood things, like Academy Award dinners. Anybody can figure that out. I did 9 million movie premieres. I did green rooms for every star you could think of I did... Like, it was a weird life. I also worked as a canine trainer at one point. I was the yutz in the suit getting chewed on by the dogs. You know, if it's some sort of industry, I probably dabbled in it to survive at some point. And the catering world was not kind to my trauma history and risk level towards substance use. I had already been coping with life a little too early and a little too much with substances, especially alcohol. But I had a really big like, I just don't give two craps about whether or not I make it till tomorrow, not actively suicidal, just kind of indifferent and apathetic to my existence, because it sucked. And, and then I, somewhere along the way, actually when I got to the point where I was sobering up a good decade of my life, and I really couldn't tell you, chronologically where I was or what I was doing. I have vague-ish timelines, but I don't know; I was a mess. And then at some point, I was like, You know what, I really like anthropology because people are fascinating. And it's not like head shrinking people; you can like, I think, I think the appeal of being someone who writes ethnographies for a living was like, Yes, send me to the pygmy tribes in the middle of nowhere and let me just hang out with like banana leaves and people that are uncorrupted by the rest of this world. And and let me learn a thing or two and try to enlighten other people. And then it was, then I had a fac... then I gave up on people entirely for one period, and I was like, I'm going to study renewables and orangutans in like Borneo and never come back. One needs a few degrees in order to do things like that, you know, so I had some fits and starts in community colleges and various places that I landed, but never quite got anywhere, landed in Storm Lake with my ex wife. I thought, all right, I'm gonna go back to school and online. In my research, the school I had had an anthropology program at one point, everyone's telling me, I'm hallucinating this, but even my wife who's worked there for a really long time can't remember an anthropology program at this school. And sure enough, there was no anthropology program at this school. And I was like, well, crap. Now what? What's the closest thing to that. If I leave the apes out of the picture? What do I do? And so it's like, Alright, fine, I'll learn psychology. Maybe I'll be a researcher, and an academic and, you know, reaching for the stars at this point. I'll be one of those PhDs that like, does research for people, I don't have to actually interact with folks. I was dead set on going academic, you know. And then I got a job as a peer recovery specialist, just honestly, out of desperation, and a need for it sounded kind of interesting, and maybe I can help other people who are struggling with addictions. Because at that point, I think that was like around 13, or 14 years of sobriety for me. And it just sounded fascinating; it was a part time job, great, I can make some money and go to school, yada, yada. I stepped one foot into that family treatment court, and was like, oh, no, I like this. And I had a really good mentor who was a co-occurring clinician. Mett is still a very good friend and mentor at this point. And sure enough, she got her little hooks in me. And it wasn't long before I was testing for my CDAC certification. And then I was a full time counselor. And then I joined the master's program, and we're like, yep, this is just gonna go all the way. And I was like, okay, but I don't really want to be like a therapist, therapist, like, maybe I can do trans research. And I can, I still had in my head that I was gonna go this other direction, while I'm actually doing the clinical stuff that I swore up and down, I was never going to do. And darn it, I'm good at it. And I know that sounds like a really weird statement, but this work is heavy. It's beautiful. Don't get me wrong, it's beautiful. But it is also incredibly heart wrenching. I have watched people give up on themselves and then helpless as a clinician to do much of anything about it, because it's their choice to a degree. There are safety measures, there are mandatory reportings, of course. But there's also this weird gray area, especially in substance counseling, where wanting to drink yourself to death is not the same thing as suicidality. And being done with your life, after decades of being an alcoholic or addict, and not knowing, or being able to even fathom any other life, no matter how good of a relationship you have with your clinician, some people just don't want it. It's too much. And they give up. And there's nothing you can do but respect their choice and do everything you can to try and bring them out of it somehow. It's a weird balance. And there are some days, especially in the early parts of the career where you're like, "how do I carry that? How do I carry this story I just heard from this person who you know, experienced incredible traumas in their lives? How do I make space for the guy that wants to tell me every single moment by moment detail of the domestic abuse he carried out?" Because it's somehow, it's therapeutic to him. And what do I do with that? And then imagine that in the middle of all of this crap, right? And so there are some days that I don't know what the hell I'm doing, and why I've done it. But the really long way back around the beginning of that question is, honestly, I don't know. It happened to me. One thing I often tell my clients, especially clients with trauma, because a lot of trauma folks have a great deal of hyper vigilance. A great deal of situational awareness that's maladaptive. A healthy dose of paranoia. No, but those were survival skills. My level of hyper vigilance has now become a superpower as a counselor, right? That same level of micro awareness to any sort of disturbance in the Force, helps me help other people. And so there's some hopeful parts to it, right. But it's still a great deal to carry. And I'm still on on probably every day, some weird vacillation of, I don't know if I can keep doing this, and I don't know if I can't keep doing this. And I have since gotten really involved in social justice, even more so than I already was, which if you have any understanding of where I came from, which is a very conservative, very military, very right wing environment, to being a social justice warrior of sorts, in my own way, it was a really long distance there. So for me to be any kind of activist is rebellious, as I'll get out. And that's not why I do it, I do it because it's the right thing for me to do. But sometimes my days are heavy enough that that's the direction I really want to go. I want to be that guy that does those talks. Someday I'm going to do a TED Talk. It's on record right now. It's going to happen, you know, I don't know how long I'll stay a clinician, primarily. Because I feel like there are other directions I could go. And I think that job will eat you alive. They think it needs a balance. I think that's part of what's wrong with the industry. It needs a balance. That's why it's so burnout, heavy well, that and the way the insurance and community mental health industries are set up, they're set up to churn through people. It's not about helping folks, it's about money. I have no idea. You know, somebody asked me like, What do you what's life look like five years from now? I don't have five year plan because I have learned my lesson. There's no such thing as a five year plan for me is just as I say, I'm not going this way, or I'm totally going that way. The universe is going to play games. So I'm in the here and now. You know, and where I'm at right now is trying to hang on for the last four weeks of this program and get all my homework done, which is going to be a miracle in and of itself. I'm a bit behind right now. And I'm gonna go where it takes me. I'm doing research, I'm doing advocacy. I'm making a name for myself in trans health equity, especially mental health equity. I work at the school district because it is an incredibly diverse district. We have in a town of maybe 10,000, in the middle of nowhere, Iowa, 30 languages spoken in our school system. And we have about 3000 students. So if that tells you anything, this is a meat packing town. And with that comes an incredible amount of diversity, because nobody else wants to work there. And give me one second I hear pitter patter. Yeah, I don't... I just don't know what to predict what comes next. I just don't. I go where, where it feels like the right thing to do, and, and still allows me to balance with my life. And I work in that district, that's where I was going, because they're, in that diversity is an incredible amount of trauma. Because folks don't just like hey, I want to go work for a meatpacking industry. They're running away from something. They're seeking asylum. They're refugees. They're living in such poverty conditions, or lack of opportunity conditions or both, or all of the above. And they need a different life. And they want to provide for their families. And we have families that walked country after country after country after country to get here. Which for those of us who are a little sideways about living in Iowa in the first place... super grumpy about it. You know, you're kinda like on one hand, like, "why? Why the middle of cornfields? Does that sound like a good idea when you come from an island?" But it's also a predatory kind of business that wanders all over the world, convincing people that this is the place to be and has big old dollar signs to back it up, and then turns them out. So, you know, we have kids, who at nine years old, walked across 12 countries to get here, and then were separated from their families for months and months and months, and then ended up in an aunt's house, that they've never seen before in their little lives, waiting for mom to get out of detention, waiting for immigration to let her go, or send her back, or do whatever they felt like doing. And that pandemic, and Trump era of that really restrictive immigration, that was just a nightmare for kids in this district and their families. And, you know, we've got trafficking victims that now cut up hogs for a living. I'm trying to pretend like all that never happened to them. We've got folks that don't speak a word of English, trying to put their kids through a better life, while they toil away like slaves in many ways. And it's just this really unique setting and atmosphere. And there's an immense need for people to give a crap about it. And so we have for this little weird area, an incredibly robust activist network that fights for these folks and tries to help with immigration issues and tries to give people access to services when they don't have a document to their name, or certainly not a legitimate one, you know, tries to help with all this trauma, tries to deal with being a rural district that doesn't have enough money for anything, you know, tries to bump up the access to mental health services, tries to offer enough linguistic services. I mean, it's this just this big cesspool of need. And it's the right thing to do. So somehow, I ended up doing that I can't help myself. I don't know where that leads. I now have a stepdaughter who's just starting high school, and then I've got four more years before I have a choice of where I live again. And I'm going to do everything I can to help the people that are here. No idea what I'm going to be where I grew up.

Kit Heintzman 42:55

What's fatherhood meant to you during the pandemic?

Gus Raymond 43:00

You know, because of the divorce, there were some natural obstacles to being able to remain involved in my step childrens' lives. And, sure, technically, they were my step kids, but they're my kids. And to a great degree, I ended up inheriting a lot of that for a while. And then two of them have aged into adulthood. And the other two are with their biological father, who have developed a really good relationship with, and so I continue to see them. But that frozen in time world that we experienced, was really hard, because we already had this weird dramatic distance that happened. And then we're just starting to get back to the point where, okay, things are established, I'm able to go back and forth, we're able to spend some time together, I can juggle the older kids and, you know, they've kind of like peeled into their own little areas of life a couple hours away, and my wife has kids, you know, that come and go a little bit. And so it just all became this like patchwork of like, figure out how to spend time with people and not lose that. And then the world stopped. And the two youngest ones are only about six hours away. Could have been half the world, didn't matter. What am I gonna do? You know, drive six hours see them at park. Like we didn't even know if that was okay for a while. And, and so there's a distance there that's really hard to live with because once it sort of sets in, it just sort of stays there especially in that teen transition where kids are kind of finding their autonomy and their independence and they're not talking every five seconds and really only call you when they need money or occasionally remember a tube or a day or something like that. I don't know how many times I've apologize to my parents at this rate. But it means the world to me as heavy as it gets, as distant as it feels, they're my world, and I adore them. And I would do anything for them. And I think they're proud of me. And that really matters to me. And I'm incredibly proud of who they're becoming. And I feel like I had something to do with that. And that's kind of the same and kind of very different to how I view my work with the kids at the schools. Right, like, they're all my kids, to varying degrees. And in the course that my life took, I was unable to have my own biological children for various reasons, and these kids are as close as I'm ever going to get. And there's a finality to that, that's really hard to carry around. And to, to have that level of relationship that we had, and then having it interrupted by all of this trauma and endemic has felt a little lonely in some ways, because I just can't connect the way I used to. It's just hard. And they're busy. And they're teenagers and missing a ton of their life. And I occasionally get super sympathetic to my parents that I clearly didn't communicate enough like when I was this age. Some part of me is like, this is a natural progression. And part of me is like, they think I'm being forgotten. For various reasons. I mean, there's a whole bunch of stuff involved in that, right. But those kids mean the world to me. And I'll, it doesn't matter. Like I'll be there no matter what, and they know it. I know they know that. That's the comfort that I keep, they can call me, anytime, day or night, months from now, years from now, weeks from now, it doesn't matter. I'll be there. And I have been because it's happened. And they know that, they know I will always show up. Then that's something I don't think that their biological parents were able to give them very much. So I take comfort in that part because they know they can always call; they don't, little buggers, but they can. I really do apologize to my dad a lot. I'm sorry, pop. It was the other hard part of this whole mess. My father lives four hours away from me. He's 75, in a couple of weeks, had a heart attack in 2019, pretty massive one he shouldn't have lived through. And so by early pandemic, I'm like, Are you kidding me? So that was a great deal of stress as well. And being separated and really worrying about coming anywhere near him for you know, very legitimate medical reasons. And he doesn't treat himself as good as he should, so he's kind of on the edge of fragility sometimes anyway because he's stubborn. No idea where I get it. And, and then kind of like the relationship with my kids, it just sort of stays that way. Like it becomes your new normal to not talk as often and not be able to see each other, to have only gone fishing once in a year. You know what I mean? Like, that's not us. That's not... we were every few weeks, I'd find a reason to go camping with my dad or go fishing or hanging out on the boat with him or help him with something or drag him over here to help me with something. Like, you know, and, and in that hopeful period last year where we kind of look like we really were coming out of this and everything was going to be okay again, I gave him, my wife and I took him to his very first football game at Lambeau Field for Christmas on Christmas Day, as a matter of fact, and he never been to Lambeau Field in his whole life, and he loves the Green Bay Packers. He loves football. And when we showed up with the tickets on Christmas morning, all he knew was that we were coming he just had no idea what was going to happen. And we showed up and we told him he was going to Lambeau and the man bawled. So whatever happens in the rest of the stupid pandemic, I got to watch my dad look like a little kid having the greatest time of his life on a miraculously warm Christmas Day at Lambeau Field, and we won. So it was all totally worth it, but even with that highlight, it's still this weird... I think everybody's just in this strange apathy and you just don't have the same connections you did. It's hard, you know, between the divorce and the pandemic. I joke all the time, like, I don't have any friends. Nobody calls me. Hey, you want to go to lunch? Look, I don't know anybody like that. Just, and I'm sort of an introverted like, antisocial 'get off my lawn' kind of person as mostly a joke anyway, it's really just a protective buffer... don't tell my wife. And, and yet, at the same time, to not have a single person for periods of time be like, Hey, how you doing? What's going on? Nothing. I think that's the cost of this pandemic. What little shred of social stuff I had rebuilt after the divorce. Gone. I have a co worker that occasionally talks to me, she's basically like an extra kid. You know, I'm friendly with folks at work, but I don't have a community here. For all that stuff I do and all, you know, as involved as I get. I'm still strangely on the outside. I'm not sure why. Combination of stuff, I guess. And everybody just sort of got antisocial in general, in this whole, in this whole experience. So... to weird life, this current post pandemic picture is.

Kit Heintzman 52:07

How did your relationship with your clients change?

Gus Raymond 52:18

Some of them became closer; some of them got lost. And you learn to protect yourself by compartmentalizing that. Tell yourself all those clinician things that everybody tells themselves like, only so much you can do, you can't work harder than the client, the choice yada yada, anything to make it feel like you didn't just lose the person and fail miserably. Some became so needy, that it was probably boundary pushing, because they just needed that connection so much in so many different ways. And they have limited ways of getting hold of you, and there's a bunch of rules, especially in community mental health; private practice is a little bit different, a little bit more lenient, still within the ethical boundaries, but you got a little more leeway there. And you're not seeing 11 people a day, but a lot of the clients became really just sort of remote, both literally and figuratively. A lot of people slipped through the cracks because there were huge gaping cracks in the system, especially on that community side, where, you know, you're operating as a county agency, in essence, and the infrastructure just wasn't there. You know, in probably six months into using telehealth, I think entities like Medicaid were like, Okay, that's enough. Like we need to go back to normal. I don't know. There's some sort of they make more money or whatever. It didn't have anything to do with people and had to do with whatever they're like, we can't give this kind of permission and access, like, oh my gosh, why would we do that? I don't know that that's what we were doing. But okay. This is one of the reasons I love community mental health. I can't, you can't, it's like a lite version of working for the SS like it just sucks. You can't do it. It's not really built to help people. And I couldn't keep looking at myself. You know, here's all of this need, arguably some of the neediest communities and populations there are because nobody else chooses to go to community mental health. They have other choices. And you're supposed to try and help them with incredible amounts of productivity, which is a word I never want to hear again in my life, and one arm tied behind your back and no resources. In a three hour radius, there are three Medicaid approved treatment centers that can send people to, there are no psychiatric facilities that can send people to beyond a 72 hour hold for suicidality. I don't care how much you're suffering with schizophrenia, there's nowhere to put you unless you're actively psychotic and a danger to other people. Not necessarily yourself, because they don't seem to care about that part. Right, like, and so people just got used to being on their own again. And a lot of them slipped through the cracks. And there's nothing you can do. You have a person who desperately need services, they're hanging on by a thread an hour away from you. The only access you have are telephone calls because they don't have a smartphone, and they don't have internet access. And they don't have the money to pay for those things, even if they could. And they don't have the access to the systems that carry those services. And you're stuck on a flip phone with somebody struggling through a couple of decades worth of really significant drug use. And you're trying to get him into a treatment center. And you keep having to tell him to just hang on another day or two, just hang on another day or two any minute now, I'll get the answer, any minute now. There are 32 freakin bats in a three hour radius, and we're on a six week wait. What am I supposed to do with that person? How am I supposed to somehow keep them hanging on that flip phone thread and not demolish themselves. Because what that feels like on the other end, is nobody gives a crap. Nobody cares if I live or die. That's what it feels like to them. And the pandemic did nothing but heighten that and highlight it and shine big glaring spotlights into those ginormous gaps in the system that we have. And it still is just now getting to the point where they're like, gee, we should probably do something about mental health. Huh, yeah, maybe we should. Maybe we should not have downsized it left, right and sideways over the last few decades and eliminated every resource we have. And then now politically act like that never happened. We just didn't choose to put the resources in the right place. No, you actively eliminate.d them, but okay. We'll play that game. I get very angry about this stuff because to them, it's policies and dollar signs and procedures and quotas, flip and productivity. And to me, it's people, neighbors, community members, parents, children, little kids that don't have a choice. Suddenly, they're ripped out of their homes and removed by the health services because mom and or dad can't stay sober because the world around them sucks, and the addicted room feels better. And everybody took a big giant healthy stare in all those gaps and deliberately closed their eyes and tried to go back to normal. And I know the school system is going to do the same thing to me, but right now, I'm still on the positive side of the equation, and I'm pretending really hard like it's not the same sort of catastrophe. But it's a little bit like it was when I first entered like they need us. I can't look at those kids and go I'm gonna go make $200 an hour in a private practice. I could, but I can't. It's like somebody took the curtain away. You know what I mean? Like, there's, there's Oz right there, little dude behind the curtain mucking everything up. And people are willfully ignoring it because there are other very important catastrophes happening as well. You know, we've got famine across the world. We've got war in Ukraine. We've got a political landscape that I don't even want to think about. We've got people fighting for their reproductive rights. We've got this huge, like boulder that any minute now may or may not come tumbling down the mountain that the LGBTQ folks and all their rights that we got in the last few years. It's just too many things are on fire, and there's not enough extinguishers. So you just do the little stuff and you hope people don't get lost. That's all you can do. That's depressing.

Kit Heintzman 1:00:33

How have you found yourself navigating sort of slippery boundaries and neediness over the last couple of years?

Gus Raymond 1:00:41

I wonder if that's why I keep myself so busy because it's just damn heavy. You know? Bizarrely, we don't spend a lot of time psychoanalyzing ourselves. If anything, we actively try to just do it on everybody else. I don't know I like I said earlier, I think it's a little compartmentalization, right? Honestly, there are just so many damn things on fire, that you kind of can't give that fragility that much time. Because if people are choosing to sort of allow themselves to sink under the water, so to speak. There are so many other people that are fighting like mad and trying to tread water, and you don't get a choice, kind of, like it's just the need in every category is just so much bigger than it was even three years ago that you can't spend a lot of time thinking about that fragility and that distance and that hanging on by a thread, you just can't, it will eat you up, so you just keep going to the next thing. You just keep going to the next person, you keep going to the next fight, you keep going to the next advocacy, you keep going to the next emergency, you keep trying to find the next connection in the community that will weave that net tighter because they're not coming to save us. That is really evident. We're gonna have to figure out how to do it ourselves. And I think if there's any positive lesson that came out of all of this, it's that this community at least, has realized they're not coming. They're not coming, so we've got to do it ourselves and find ways to take all these little pockets of resistance and support systems and knit them into our own net and save people that way. But the theme has become relationships, that's what we've been talking about for the last year, year and a half. It's about building relationships. It's about that one on one connection. And that is going to be the thing that makes the difference and builds the nets. Because the big giant versions of you know, advocacy and community organizing, just people don't have the energy for it. So it's going to have to be a neighbor by neighbor kind of effort at this point, and I have seen some incredible collaboration over the last year. Working with the county public health folks that none of us have ever really worked with. Everybody was all in their little silos. If there's any positives, it's that like the silos are broken down. People are really trying to help each other out on this micro level. It's the bigger more regional, state and global level that's still just a mess. Yeah.

Kit Heintzman 1:04:14

You've mentioned the state not handling the pandemic especially well, what are some of the things that you noticed that bothered you? Or some of the things you'd like to have seen different, done differently?

Gus Raymond 1:04:25

God, all the rhetoric almost instantly about whether or not it violates your rights to have to wear a mask somewhere, whether or not.... I mean, it was just like the, not to get super political because I try to avoid it, but that that right wing Republican rhetoric, all through the pandemic of don't violate my rights, while I stomp all over yours, because I can't be bothered to wear a mask in Walmart inn the name of freedom is just unbelievably annoying to me. It was sanctioned from the very top. And people spent, and the government spent so much energy actively fighting places that were just trying to protect people to go back to normal because the economy can't trickle down. The way it never does. I mean, it was just astounding to watch them fight common sense. Like to watch them actively sabotaged public health measures, and act like the experts were morons. You know, 'internet Joe' knows way more than Dr. Fauci because he studied it on Twitter. That doesn't even make sense, and yet, it's the way things are now. I mean, instead of being a fringe argument in the middle of a pandemic, where everybody's freaked out, and it's sort of excusable for people to act a little bonkers, it's now the way things are. That's the platform they're running on. And one way that gets illustrated to me is, in the same way as they fought the protections during the pandemic and actively refused to distribute the rescue funds. As a matter of fact, our governor gave back $800 million to the federal government instead of giving it to Iowans because she was so stubborn about this political tactic. I don't even know if I understand it all, but it was just like, you got to be kidding. There are people here lining up for food boxes, several days a week, every week, and there are more and more people coming, and we gave the money back. Like what universe does that make sense? And there was nothing you can do because no amount of yelling and screaming and advocating and fighting made a dent in the fact that we have a completely Republican controlled legislature and a completely Republican controlled governorship. It's like spitting in the wind. I live in the district that was formally Steve King's for over a decade. Like that alone illustrates where I'm at. Why does it hurt anybody to protect people a little bit? Like it doesn't even make sense to me. And then they just switch gears. You know, last legislative session was, if I remember correctly, the most anti-LGBTQ, legislatively speaking, than we've had each year in the last three or four years has been progressively more and more anti bills. And we fought really hard this year and barely made it on several close calls. And it just, you know, the door is closing. You know, the momentum right now is let's do more bands. Let's, let's restrict trans kids even more. While we don't allow you to protect yourself, and we don't allow you to wear masks, and like it wasn't even like, it wasn't even like some places you can choose and some places can't use; it was if you choose to protect your business and have people wear masks, we're actively going to come at you and force you to stop that in the name of freedom. We're going to tell you, you can do the thing you want to do. Yeah, that's about it in a nutshell.

Kit Heintzman 1:09:20

I'm curious, what does the word 'health' mean to you?

Gus Raymond 1:09:29

I'm a Holistic minded person and clinician, so health to me is not a one way street, and it's not a one dimension concept. Health is synonymous with wellness, and it is a basic human right. I do not understand the concept of restricting access to things that make people feel healthy and well. I don't understand the concept of making that 10 times harder than it needs to be. And I don't understand why some people deserve access, and some people don't. And there's not even a real good rhyme or reason. Other than the obvious, ah, you know, discriminatory platforms, there's not a rhyme or reason for it. It's essentially we just don't like other people, whatever that means to whoever's in charge. And both sides are guilty. Health is humanity. And for some reason, we restrict it on a global concept, sure, it's super idealistic, but the fact is, there are enough resources, financially, economically speaking, to completely end world hunger. It's here; we have it. We absolutely have the ability, and we just don't. We just don't. We just watch people get massacred or die of famine. We send a couple of Red Cross trucks and we talk a good game. We could end it. And we don't. And then we have these stupid political arguments about who gets access to health care like... I don't know, my sense of justice tries really hard to keep fighting, but occasionally, if I allow myself to glimpse that bigger picture, it's just like, What am I doing? Why am I even trying? I can't not try, but what's the point?

Kit Heintzman 1:11:57

What do you think are some of the things that would need to change to end up in a world where we decided that global hunger was a problem worth solving, given that the resources are there, what would, what would it take to make up for us to make that decision?

Gus Raymond 1:12:17

As much as I fight for those things, and I have that idealism, and I have that sense of justice, and I can't stop even though I know it's completely hopeless, it's completely hopeless. Like at this point, it just is. It would take a fundamental shift in, in humanity, in empathy, in emotional evolution, to get to that point. Even indigenous cultures struggled with that to a degree right? Tend to put most of those cultures kind of up on a pedestal of like, it was all Kumbaya, spiritual, and whatever. They had wars. They're human beings. They fought over, sometimes silly things, in retrospect. But, in general, they found ways to coexist because they weren't so, I don't know, overpopulated as to deplete things in the first place, and maybe that's where we went wrong. Maybe it's just a numbers game, I don't know. But people just can't not hoard it. There's across cultures, especially in the Western cultures, there's this epidemic of greed that, if that does not fundamentally change into a more collectivist attitude, we're not going anywhere, because they're the ones with all the power and the resources and the folks that think differently, don't have the power and don't have the resources, enough to change the equation. It would take a fundamental shift in that. And I'm not so sure anymore that we're capable of doing it. Global pandemic didn't even spur us in the right direction for too long, so I don't know what it's gonna take.

Kit Heintzman 1:14:38

What does the word safety mean to you?

Gus Raymond 1:14:49

At this point, I don't even know how to answer that. As a trans person, it means a lot of things, as a clinician, it means a lot of things, as a husband and a dad, it means a lot of different things. I mean, it's kind of different in each one of those equations, right. Like safety for me is in my current existence, living where I live without an LGBTQ community and being a very passable, cisgender looking male who could just wander about town without a care in the world. In some ways that safety for me, and it also feels disgusting, because I feel like I'm hiding. But it's also out of safety that I do so. And don't get me wrong, I do a ton of advocacy, but people have short memories around here. It's weird. It's like everybody knows, to a degree, who and what I am, but as long as I'm not back on the front page of the paper, like everybody sort of pretends like that's not the case, in a weird way that keeps me safe. And it keeps my wife safe. I hate when she gets flack from my advocacy and my existence as a trans person. And maybe unconsciously, that's one of the reasons I don't speak up more and loudly or louder than I do because I already kind of run my mouth. You know, it also means normal basic human rights, it just means being able to walk down the street, it means knowing there are going to be resources to feed my family, it means I can access health care when I need it. You know, I mean, super fundamental, basic human rights, but it gets really complicated depending on your circumstances. You know, in light of the Uvalde shooting and all of the other shootings, you know, that's about the same timeframe that I started working in a school district, and what was clinically for me pretty good awareness of that circumstance and that level of safety risk, you know, is now reality, because one of the first things we did at the end of the school year was start practicing active shooter training drills and having workshops about how you get through that. And if that didn't submit some reality in your face about safety, I don't know what would. That's a new climate, and, and I, you know, like I said, I grew up in a very conservative, very military, that everybody had a gun kind of atmosphere, so it's not like it's foreign to me, although it's foreign to me in a weird way. But thinking about safety has yet another connotation now, because of my job.

Kit Heintzman 1:18:04

There's been such a narrow and focused idea of safety in relationship to pandemic precautions, thinking in that teeny, tiny speck of what safety can mean, what are some of the things that you've been doing to keep yourself and make yourself feel safer over the last couple of years?

Gus Raymond 1:18:25

I think that's the level of isolation that I've grown into, you know, part of its outer stuff, and part of its inner stuff, right? Like, like I said, I'm sort of naturally introverted, stay at home kind of person, because I already did that, wild it out kind of life. And it just became the way things are, and that feels safe to me. And there's also a portion of me that's just so damn tired of this, that I sort of throw my hands up and go do you know, the event anyway, whatever that event is. You know, part of my brain says, if I go, X, Y, and Z do I need to wear a mask; you know, there's sort of a hands up in the air, screw it kind of attitude to a degree because you're just exhausted. And, and so I don't know if the early pandemic version of safety where you have these like really rigid tools that you could use, right, you could isolate, you could test you could mask up, you could pick up your groceries, you could, you know, there were all these like things you could do, and now, we're just sort of in this weird, vague blobby zone of like, I mean, do it if you want to. Some days you feel vigilant. Some days you don't. You can't keep watching your kids sit on Snapchat forever. They occasionally need to go do stuff. And there just becomes this momentum especially in the atmosphere in our state that's like, what are you gonna do? You get it, you deal with it. Like, and, and where does that safety equation drop off where you're responsible for other people? Like, it gets this, I think it's like everything else; it just gets so overwhelming and complicated that you're just like, whatever. The more you stay at home, the easier the equation is. I don't have to worry about it. I don't have to worry about if I look like an idiot wearing a mask, if somebody's gonna yell at me, if somebody's gonna get in my face. It's even allowed, like some places will even like try not to let you wear m- it gets just bizarre. You can't even practice your own... like I said earlier, like in the name of freedom, you can't practice your own safety measures. Like you actually get crap for that. So most of us just stay home. I haven't been to a concert in ages. I'm taking my wife to you know, a birthday dinner, and a little jaunt into the casino felt like naughty. Because we haven't done anything like that in so long. I don't know, safety feels like a luxury, I guess, at this point.

Kit Heintzman 1:21:19

Would you share more about what it felt like to go into the casino for your wife's birthday?

Gus Raymond 1:21:24

You know, this mixture of excitement and dread. The one thing I do know is casinos spend a lot of money on air filtration and that was probably one of the only things that made me feel a bit more comfortable. And a little bit of I'm pretty sure we probably got over COVID a couple of weeks ago ourselves because we both had nasty colds with the exact symptoms but kept testing negative on the home tests, and so we kind of like we just acted as if even though the test kept saying no. And so I think there was a degree of safety in that because typically speaking in that early window, you generally don't contract that again. And so there was a little bit of immunity feeling, so I felt half naughty and half like grossed out all the same time. You know, and it's, I'm a little sensitive to being around crowds anyway, I always have been. And, you know, occasionally we'll struggle in like an auditorium or something like that, but I think the nice thing about yesterday was, although I felt a bit of apprehension walking into that atmosphere and that many people, I think they have made some adjustments, and so things feel a little more spread out than they used to than I remember them being anyway, and so I didn't feel a level of intrusion. And really, I just tried to focus on is my wife enjoying herself, is she happy, does she look lit it up? Because that was the whole point. I didn't care about the rest of it. I could go or not go; it doesn't matter to me. But I was trying to do the things that she loves and that we haven't been able to do much of and, and so it felt like an appropriate risk. And I don't feel guilty about it, because we had fun, and she had a nice time. And like I said, I think relatively speaking, we're fairly protected at this moment. I don't know that I'll go out and do it again in a month, but the important part for me was watching her be happy and excited because it feels like there's not a lot of that these days.

Kit Heintzman 1:21:42

How are you feeling about the immediate future?

Gus Raymond 1:23:48

It vacillates. I think given the conversation, probably heavier than I would normally because I try to not let myself look at those bigger pictures, but regardless of how it ends up feeling, I still have to just keep working forward. That's just all there is to it. There aren't any choices for that, so I feel cautiously optimistic, I guess, if I had to kind of break it down into a phrase, and yet, super fed up. I don't know what normal looks like anymore, but this doesn't feel like it. And I would like it to get there. That would be great.

Kit Heintzman 1:24:45

What are some of your hopes for a longer term future?

Gus Raymond 1:24:48

To make a difference. Really, I mean like I said, I've learned over the last few years not to like really get my heart set in a certain trajectory and make it real specific because that, the universe has other plans. And I don't always get to know what that is, and I kind of have reached this weird point of like, I'm actively doing the things I feel like I need to do, but it's a lot more instinctive than it used to be. It's not logistical and practical and like, calculated, it's gut. And like, when I was offered this job, it was an absolute gut reaction and like, yep, I need to be there, I need to do that. That's perfect for me. I just want to make a difference; I want to change the trajectory of some of these kids lives, I want to, I want to make some incremental, small, even tiny little dents in the atmosphere of anti LGBTQ legislation and rhetoric. And maybe some of the research projects I work on can do that. What I absolutely will not do is stop advocating, even though a big chunk of me is like, what's the point? But I can't not do it. So whatever that looks like, I'm not real sure. I'm going with the flow here, but I can tell you for sure, I'm not going to stop.

Kit Heintzman 1:25:53

Who in your life has been supportive of you, over the last couple of years?

Gus Raymond 1:26:47

My wife. My wife is my rock moreso than just about anything and anyone else, you know, my mother and I don't have the most, I don't even know what to call that, it's pretty fractured. And my dad, like I said before, is just things just become sort of distant and like meh everywhere, but she is my constant. She is my constant. And that, and the impact I have at work, those are the things that that really refuel me, although I have been really exhausted. And I think it's just I'm on that last stretch of this program, like I said, and, and things have just been so heavy in the last few years that it's like, this is that last mile of the marathon that is really hard to run. She makes that analogy for me all the time. So I'm, I think I'm feeling that. But somewhere in last night, I was like, You know what? Not real sure how I'm gonna get through, practically speaking this next four weeks and the amount of work I have to do in order to complete it, but I do know, I'm going to complete it. I don't know what that looks like, and I'm not real sure how to make it happen, but it's going to happen. I did not come this far to fall on my face

Kit Heintzman 1:28:24

What are some things you've done to take care of yourself?

Gus Raymond 1:28:27

I don't, to be perfectly honest, I don't. I should, and I know I should. But there just isn't a lot of room. And so I think I've adopted over the last year, for sure, adopted this sort of mentality of just like just, just keep swimming. We're gonna get to the point where I can do things like go fishing, and go kayaking, and go to a gym. And I look like I've got a dad bod, like, but things are on hold right now because I have these other parts, and there's just only so much room in the equation. And sure, I could probably manhandle in some self care time, but I don't think it mathematically works right now, so I just do the best I can do, and I take little bits and pieces. Normally, I'm the first person up, there's a period of quiet time there. I probably ought to be productive, but I'm not. I putz around on my phone. Some days I doom scroll, and some days I play games. Some days I take the dog for a walk. Just whatever feels right in the moment. Then, I put my hats on, and I get to work. And that's probably the closest to self care I've got at the moment. I am living for that period of time where this is over, and I can feel that sense of freedom again. Then I can choose to do some of these other things. They just don't feel possible right now.

Kit Heintzman 1:29:59

Has your relationship with your dog changed at all?

Gus Raymond 1:30:03

This is the neediest little creature ever. She's a rescue. She... I've had her probably about six months now, seven months, so she's a newer addition to the household and is absolutely like neurotically obsessed with me in particular. I don't know if that's because I don't, I don't know. I don't know. Dogs usually like me as it is, but like, she will legitimately run right past a very excited teenage stepdaughter who's so like, come here, and run right past her and walk up to me, like, nobody else exists to a certain degree, which is kind of annoying but also really cute and probably just what I need, in many ways, but also gets like, a little old, sometimes, like, just just lay down. Like, I know, I got up and moved two feet to get my glass of water, but everything's okay. So, we're working on it, but she's, she's my little pal. She's fun.D

Kit Heintzman 1:31:12

Do you think of the pandemic as a historic moment or historic event?

Gus Raymond 1:31:31

Kind of. I mean, it was clearly pretty disruptive, like any other global catastrophe would be. But at the same time, it's also sort of like, I guess some of the response level, especially in the US has been a little bit like, yeah, that's predictable. That sort of par for the course for us, we talk this great, like, we're the best there is, we're the shining star of the globe, and yet really struggled to back that up in almost every category, that, you know, in some ways, it's like, it's just another one of those blips on the, on the timeline. There are a lot of things we, we keep getting these opportunities, and we kind of keep blowing it, historically speaking. The universe gives you one more chance to like, change course, correct your trajectory and like, you know, do the right thing, and a huge chunk of us just keep going eh, we're going this way. Just okay. You know, it's gonna go down, it's gonna be part of the history books, it's going to be a very big deal, but at the same time, it's like yet another one of those spots on our timeline. It's just like, really could have done that differently.

Kit Heintzman 1:32:59

What are some of the things when you were growing up that you learned more about in history?

Gus Raymond 1:33:06